For most of my childhood and early adult life I was always sick. My parents were so concerned about my constant sniffles that they had my tonsils removed at 6 (a popular procedure in Japan and Taiwan at the time). For awhile that seemed to do the trick but then I started to pick up weight in college and then suddenly it seemed like I was sick all the time.

This little “emergency bag” had fexofenadine (Allegra) to deal with sudden allergic onset, benadryl to deal with runny noses and to help me sleep, pseudoephedrine to last me 24-hours until I can get to a pharmacy, ibuprofen for fever, and cough drops.

My three years of law school was spent in misery where I would catch colds 4-5 times per year with each episode lasting 4 weeks. And when it wasn’t the cold, it was allergies, and it left me in a fog all the time and unable to concentrate before finals. Naturally, I developed several responses to this, with a bag of drugs that I kept handy. I dutifully got a flu shot every year (and never got the flu). I also tried very hard to avoid infection, which I was pretty bad at.

But despite all the drugs and hand washing, I continued to get sick at an alarming frequency, and it culminated in a Spring Break trip to New Orleans where I was supposed to help out with a volunteer effort for the victims of Hurricane Katrina and wound up being mostly useless because of a cold I caught nearly 2 weeks before we left. Not only that, it worsened because I didn’t want to miss out, and quite a few others also got sick, though none were nearly as bad or as symptomatic. The other students nicknamed me the outbreak monkey and it was embarrassing, but I deserved it. I had indeed gotten them all sick.

So, I am qualified to talk to you about how not to get sick.

Some of you might be here for short answers, in which case you can skip to the bottom to see best practices. I’m an engineer by training, so it’s frustrating to hear people demand “just give me the answer” (remember that kid in elementary school?), and if you’re like me, you’re not content with stuff like how doorknobs will get you sick but drinking fountains won’t, or take a shower when you get home but shoes are okay, etc. If you don’t understand the mechanism behind infection, none of these answers will make sense, and you won’t remember them or internalize the proper behavior.

Coronavirus Etiology

When people hear coronavirus they immediately think SARS or MERS. The coronavirus is actually quite common. They exist among humans in less virulent strains that are little more than literal headaches for the majority of us, and because most infections are mild, no one has bothered to make a vaccine for it. The virus spreads commonly through an aerosolized (floating) droplet of body fluid or droplets that land on a surface. You inhale these droplets or touch these surfaces and sooner or later bring them to (usually) your nose where it makes its way to your throat. From there the virus invades your cells and multiplication begins in earnest. This is where you — often as a first sign — feel that your throat has gotten a bit sore or scratchy and you run off to the drugstore looking for cold medicine, which suppresses symptoms and does nothing to address root cause.

The relationship between cold weather and humidity and human rhinovirus (common cold) infections. Notice that cases spike not only when it’s cold, but during sharp changes in temperature and low humidity. Notably, low humidity in the environment dries out the mucosa and leaves the epithelium more vulnerable to infection, while excessive mucus stimulated by the cold contaminates close quarters and infects others. Ikäheimo and Jaakkola et. al., A Decrease in Temperature and Humidity Precedes Human Rhinovirus Infections in a Cold Climate, Viruses by MDPI, Viruses 2016, 8, 244; doi:10.3390/v8090244 .

Since I was such a pro at being sick, I have come to recognize that the first sign of a cold is always a scratchy throat for me. Rarely do I not notice this and go straight into a stuffy/runny nose, cough, or fever. However, people who’ve had severe cases of Covid-19 often report that they suddenly “woke up” one day with a fever, dry cough, or body aches. I think the most likely explanation is that the virus travels by aerosolized droplets deep into the lungs and began its infection there, so there are no initial throat symptoms. A paper that studied SARS-CoV (the closely-related coronavirus that caused the SARS outbreak) identified a protein called ACE2 that helped the virus bind to cells, and this receptor was most prevalent in lung and small intestines epithelia, which would explain why people start off with a dry cough (lung symptom) or digestive distress.

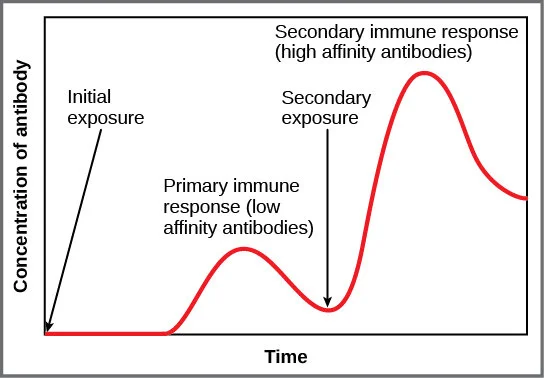

At any rate, symptoms are likely to be severe from the start because this strain is novel and our immune system has no memory for it, and is therefore unable to mount an effective defense. It’s like a bunch of medieval foot soldiers who have never heard of a cannon, and doesn’t know what to do when the fort’s being blown to bits (this is not completely true — I’ll elaborate later).

We are not completely defenseless in this. You’ll notice that one of the very effective things your body does is to secrete a lot of mucus, which acts as a physical barrier to prevent the virus from landing on intact epithelial cells that line your throat, nose, and sinuses. The worse the infection, the more vigorous this response, until your sinuses plug up and you develop what is a head cold (so you should always blow out your snot). This is why hot showers often make a cold sufferer feel better, because it clears out the mucus with heat and soothes the respiratory tracts with humidity, and the brief elevation in body temperature stimulates the immune system.

A pair of nose hair scissors. Clipping your nose hair regularly prevent itching and excessive mucus buildup and makes you more attractive on dates. Credit Amazon.com.

Another response is the cough. Coughs and sneezes are mammalian adaptations to clear respiratory infections by expectorating the mucus out of the body with physical force. When the ordinary action of cilia (microscopic hairs that line your respiratory tracts) isn’t enough to sweep mucus and debris from the lungs, you develop a cough. If the mucus is in the nasal passages, it’s a sneeze. If it’s in the trachea or lungs, it’s a cough. Viruses have adapted to this very well because these two actions produces the most amount of droplets that aerosolize or stick on surfaces and that’s how it transmits to someone else.

Fortunately, I think one of the most effective things we can do when a virus first begins attacking your throat is to prevent it from invading more cells. This can be done by keeping the throat moist by drinking water or sucking on lozenges. Many people use zinc and it actually works because zinc has unique chemical properties that prevent the virus from taking hold, and if you can control the infection in your upper respiratory tract, it won’t get into the lungs (lower respiratory) and cause pneumonia. The old advice to drink a lot of water also works, at least in the beginning. Hot water dissolves phlegm which often accumulates in the throat and stimulates the cough response. Before going to bed, pop a lozenge in your mouth and let it dissolve slowly to slow viral progress while you are asleep.

Should you be constantly washing your hands? This is another area that I think lacks nuance. There are people who think this will go away overnight by staying home with a 100-year supply of hand soap and it’s again overly simplistic. As I’ve mentioned, the method of transmission is (frequently) from droplets to hands to the oral mucosa. You can certainly reduce infections by handcuffing your hands behind your back but that’s not practical. It turns out that what causes us to touch our face with hands is irritation, and nothing causes irritation quicker than drying out your hands and washing excessively. Do not use antibacterial soap, as that can help breed superbugs. Certainly if you are out touching a lot of things, you should periodically wash your hands but if you are home there is no reason to wash them obsessively. If you can, avoid the non-heated air dryer in the public restroom, as those can blow aerosol all over the place including back onto your clean hands. It helps to wash your face once or twice a day if you have oily skin, or rub gently with a clean paper towel. To reduce nasal irritation, clean out your nose when showering so you do not unconsciously pick at them during the day. Always blow your nose by first grabbing tissue paper to separate your hands from your nose. If none are available, you can blow farmers style (one minor suggestion I would make to the video is to seal a nostril with a knuckle instead of a fingertip) and wipe residue with your shirt sleeve.

Your immune system spends a few days freaking out while it figures out what the attacker looks like so the secondary response can be much more coordinated. That’s the time your sickness worsens. Very lethal pathogens, like the bubonic plague bacterium, can overwhelm this initial response and cause death very quickly.

There is an initial time period where your immune system, like the medieval soldiers, is trying to figure out what’s bringing down the fort, so it (sometimes) sounds the alarm by inflammation and fever. The job for us here is to buy time for our immune system, and thus flattening your own curve — since your immune response to a specific pathogen has to ramp up, and for that the cells must recognize it and signal enough of its cohort to all identify it — so if you can slow down the viral invasion in the first few days, you will have a much milder and shorter disease episode. I’ll talk more about how some metabolic issues with the body interfere with these responses later, as this is a vastly complicated subject in and of itself.

Viral Loading

By now everyone has seen this graphic, which I personally hate, because it presents disease spread in an extremely simplistic manner, as if everyone is exactly the same match. In reality, some matches burn much brighter than others (super spreaders), some fizzle out (good immune system), some matches burn longer and others burn for an instant. People have different incubation periods, and when people get sick, they have vastly different responses. The goal is to prevent infection and if infected, have a mild disease episode, but how?

Suffice it to say that one virus particle is very unlikely get you sick even if it landed directly on the throat. There are just too many things that could go wrong for the virus — it’s blocked by mucosa, whacked away by the cilia on epithelial cells like a ping-pong ball, eaten by a hungry macrophage, doesn’t find an appropriate cell receptor, fails because there’s something wrong with its coding (yes, cells make lots of mistakes when making virus copies). To actually infect, there needs to be a minimum number of viruses that you pick up - usually in the tens of thousands. This concept, called infectious dose, is well-known in the literature.

The other thing is that different people generate different amounts of the virus. There is a strong correlation between very symptomatic patients vs. asymptomatic or mild cases and viral load. The “sicker” someone is, i.e. the more symptoms they exhibit, the more likely they would be actively spreading the contagion, and the more viruses they would be dumping out into the environment for the next victim. In an analysis of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) patients, caused by another coronavirus, we can see that mild cases (who breathed regular room air) had initially high loads but quickly fell as they recovered. Ventilated patients have a higher load for a longer duration (so they were more infectious, for longer periods of time), and the numbers were off the charts in patients who died. This makes sense for the very simple reason that virus growth continues until it is checked by the immune system, and poor immune response in sicker patients results in higher loads. One patient recorded an astounding 1+ million copies per mL of blood.

MERS patients and their viral load grouped by outcome. The more severe cases had the highest loads. Al-Abdely, Midgley et. al., Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Infection Dynamics and Antibody Responses among Clinically Diverse Patients, Saudi Arabia, Emerging Infectious Diseases, Vol. 25, No. 4, April 2019 https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2504.181595

So all the stuff you hear about how Covid-19 can be found everywhere — in the urine, in the stool, in the blood — does not mean that it can be transmitted if you stepped in a puddle of pee or cleaned the toilet of a patient. It just means that in some very sick patients, there are so many copies of the virus that it is spilling into the blood and other bodily fluids. This could potentially be a problem for a sanitation worker cleaning out the pipes of a hospital where he may come in contact with aerosolized stool particles but that wouldn’t be how most of us would get sick.

If there is a minimum number of virus particles required to actually get you sick, then obviously the preventative step is to decrease the number of floating copies (the ones that are by far the most dangerous are the aerosolized ones, seen from the chart to the right). We know the sickest people has the highest load and so the most concerning situation is being in the same room or breathing the same air as a coughing patient, because that’s how droplets reach the air and how they could directly go into the lungs (this is a great time to turn off your nebulizer, humidifier, or vape. You’re creating a lot more aerosolized particles floating around). If you are already or suspected to be sick, a face mask can effectively prevent most droplets from reaching the air.

Decay of Covid-19 virus particles in red. Aerosols remain the greatest risk of infection. Viral load decreases dramatically on surfaces (note that the decay is logarithmic). Doremalen et. al. Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1, New England Journal of Medicine, March 17, 2020. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973

The next dangerous situation is touching surfaces contaminated with the mucus of an infectious patient (and touching your nose/face). The problem here is that while viral loads decrease quickly, they survive a lot longer on surfaces than in aerosol. I really hate round doorknobs for this reason because there is literally no way to grab it with anything other than your hands. The key here is allowing surfaces to dry. It’s not just a truism that water is essential for life. The lack of water inactivates most pathogens quickly. This relates to the use of disinfectants and hand sanitizer and people who obsessively slather it all over their hands. If you allow your hands to stay moist, pathogens can live a lot longer on them, but most disinfectants last mere minutes (such as evaporating alcohol) before they lose effectiveness. It’s also common to see disinfectant used at the wrong concentration which doesn’t do much other than extending the time in which the surface is wet. Drying your hands is just as important as washing them, as is allowing common surfaces to dry. This is why the Chinese government had Wuhan residents open their windows even in the dead of winter, because low humidity dries stuff out quickly.

For all other activities, particularly outdoor activity where free flowing air disperses aerosols rapidly and where UV rays quickly inactivate pathogens, the concern is much lower. Don’t be an idiot and ignore social distancing. Aerosols can still get you if you do the Spring Break thing, but running along a sparsely occupied bike path should yield little risk.

Should you avoid trains and buses? Since I’ve started to ride Metro Los Angeles in 2017, I’ve only rarely gotten sick and each time I was able to attribute it to something else, like drinking heavily or running a marathon. This is likely because L.A. has a low humidity and the volume of air circulated by the vehicles is large. Surfaces like hand grips are a concern, but like I said it’s primarily aerosol and less surfaces so they aren’t as much of a concern unless you like to pick your nose on the bus. Obviously it is not as safe as driving alone and the risk increases in a more crowded vehicle, but I’ve honestly seen some pretty unhealthy Uber drivers who would probably get me sick faster in a rideshare than Metro ever will.

Educated Hypotheses

Note: The following are my educated guesses. It will take years for the research to actually come out but I don’t see downsides to some of the behavioral modifications that might be consistent with these hypotheses.

If digestive distress is also a sign of early infection, then an alternate theory of transmission from feces (possibly aerosolized from flushing) should be considered as well. I don’t presently think there is a mechanism for this to be a food-borne illness mostly because of the well-known pH whiplash your digestive system subjects to food (a stomach acid pH as low/acidic as 1 and an intestinal environment as high/basic as 9). However, many people also have leaky gut syndrome, so it’s possible for small intestinal epithelial cells to become infected and shed viroids that way.

I also have some thoughts about the epidemiology. Logically there is a very real possibility that a lot of people may have already been exposed and developed immunity to the virus, but simply never manifested symptoms or tested negative. This could happen if they were exposed in the upper respiratory tract (which also has ACE2 receptors) but never progressed to bronchitis or pneumonia. We know that SARS can both be an upper respiratory and lower respiratory infection. A Covid-19 infection with a threshold infectious dose, where the virus lands in the wrong place, would mean mild symptoms or no symptoms. Such a person would never test positive, but still develop Covid-19 antibodies in their serum, which can be detected via another (currently unavailable) blood test. As shown by exhaustive testing in China, people who are asymptomatic do not walk around with ginormous viral loads that are readily picked up by a throat swab and even the current available (RT-PCR) test has a significant false negative rate, in even severe cases where 75% of CT scans confirmed pulmonary pathology. There is concern that asymptomatic individuals could shed viroids for weeks before and after their illness, but if they are asymptomatic the viral loads are expected to be low (or else there wouldn’t be so many false negative tests). Potentially, mild or asymptomatic cases could have been building up herd immunity all this time so not everyone will be susceptible.

Best Practices

On preventing exposure:

Aerosolized droplets are the enemy. Avoid being in non-circulating indoor environments with large numbers of people.

Keep restrooms fully ventilated and dry and do not linger in public restrooms that have hand dryers.

Avoid cramped or crowded indoor environments that require touching shared surfaces (supermarket cart handles, refrigerator doors), especially those that would likely be contaminated.

Touch shared surfaces with body parts other than your fingertips, elbow, knuckles, etc.; open windows and allow showers and surfaces to dry.

If you must, go out once a day, get everything you need done, and shower and change clothes when you get home. Wet clothes should be washed and dried as soon as possible.

Outdoor environments under the sun, with proper social distancing, carry little risk.

Do not overuse disinfectant and hand sanitizer. After washing your hands, dry them. Avoid air blowers. Do not wash your hands so much that they become irritated. Rub tallow or lard on dry skin instead of lotion.

Do not touch your nose. It is best to clean your nose once a day in the shower and trim nasal hair so they do not become itchy.

On mitigating infection:

Drink warm non-sugary fluids, such as no-calorie electrolyte, coffee, or tea.

Salt water or mouthwash gurgle effectively reduce throat symptoms.

Dissolve zinc lozenges in mouth (do not chew)

Blow out snot and cough out phlegm; mucus production is protective and should not be suppressed via medication.

Do not use OTC medications to suppress symptoms, especially in the early stages; allow your immune system to respond naturally.

Do not stress your cardiovascular system by smoking, vaping, or drinking.

On protecting others:

If you have symptoms, stay home; stay in your room; do not share restrooms.

Try to maintain negative pressure by putting a fan in the window to blow outwards or turning on the vent fan in the restroom.

Wear a face mask if you must go out.

Keep used towels and dirty laundry in the closet until it is time to wash them. Keep others away while you do laundry, and thoroughly dry items.

Use humidifiers or vaporizers in your own room, away from others.

Do not go to the hospital unless you have trouble breathing. A thumb meter that measures oxygen saturation can alert you to respiratory distress.

Further Reading

Caltech: The Tip of the Iceberg: Virologist David Ho (BS '74) Speaks About COVID-19

NYT: More Americans Should Probably Wear Masks for Protection

NYT: Exercising During Coronavirus

NYT: These Coronavirus Exposures Might Be the Most Dangerous (added 4/1)

Covid-19 Part II: How to Avoid a Severe Case: The Role of Inflammation and Metabolic Syndrome (coming soon).